The energy sector and manufacturing practices have both changed dramatically since the late 1970s. And in that time, James Turner – known to all as Jimmy – has worked his way from machining apprentice with the National Coal Board to shopfloor supervisor at the Nuclear AMRC in Rotherham. We asked him to talk about the changes he’s seen and lessons he’s learned.

I started my apprenticeship in the late seventies, when this area was predominantly coal and steel. With the coal industry in Rotherham, where I was from, that was the natural industry to go into. My father insisted if I was going into coal mining, I did a recognised proper apprenticeship.

I did my CSEs and got good grades, did the interview and tests, and that was all fine. Now comes the difficult question: “What apprenticeship would you like to do?” They took you around to show the different trades – electrician, diesel fitter, underground fitter, surface fitter, mechanical, joiner, bricklayer, welder, blacksmith, and finally machinist.

I did a four-year machining apprenticeship, and worked as a machinist all the way through until they started closing the coal mines. My engineer then got me a job at an oil and gas company, and that was the first time I’d ever clocked eyes on a CNC machine. I had to go to night school, and I did three years on CNCs.

I then did five years in Germany – I took the job mainly because it was working with exotic materials, phosphor bronze and stuff like that. After I came back, I got a job in aerospace at Doncasters Bramah. That set me on the route to working with complex parts, which I found really interesting.

I got into this role because I knew that there were jobs coming through the university, and I knew that they did aerospace down in the AMRC. It was just by chance I fell on nuclear, and that’s what I’ve done since 2012. I really do enjoy my job as a shopfloor supervisor, but I do miss being on machines because it’s something that I’ve done all of my life.

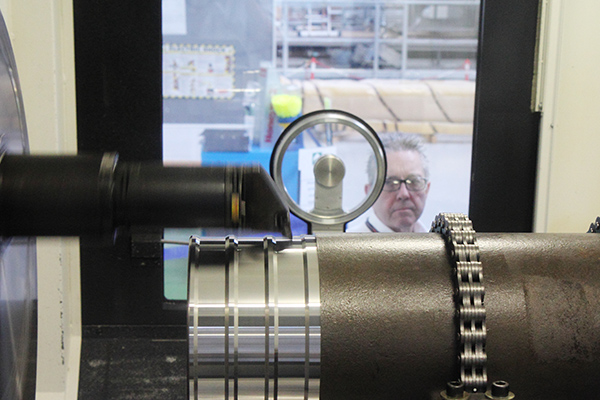

The changes to machining practices over the years have been absolutely phenomenal. Health and safety has made significant progress. For example, the machines that I used to work on had no guards on. You just had to be extra careful, even with the coolants. Many machines didn’t have through-spindle coolant, and I remember using a washing-up liquid bottle for my coolant. Some of the machines didn’t have swarf conveyors – you would have to sweep around and clear the swarf up yourself.

It was a natural progression of the advanced practices that came in when the microprocessor made massive leaps into CNC machines. The earlier machines were punch tape and just read one line – now, a majority of machines are closed in and you can’t get near them, they’re full of safety gadgets.

The advances to machines are phenomenal – each year they’re coming up with new machines. What our machinists can do with the machines today is just sheer brilliance. The calculations that the machine can make are phenomenal.

Nuclear power has also got more technically advanced, and health and safety has got a lot better. I had a visit to Westinghouse which blew my mind – the health and safety was absolutely phenomenal.

The advice I’d give to young engineers is to go as far as you can. The education system now is a lot better than when I started. I didn’t know anyone in our sixth form that went to university – you did your CSEs and you were put out into the world.

It’s a great time to come in to be a machinist. If you’ve got the opportunity, grab it with both hands. Learn as much as you can, because that period between being 17 and retiring seems a long way. I could tell you it’s not. It’s such a short period of time you’ve got to go through your life, and it’s all about learning.

Some of the guys on the shopfloor will tell you, you never ever stop learning. There’s always something else to learn.